Introduction

This is the second part of my series highlighting the myriad problems in Common Sense Skeptic’s “DEBUNKING STARLINK” video. If you haven’t yet read Part 1, head on over and check it out. A solid understanding of the performance differences between Starlink and HughesNet/Viasat is important to understanding projections for how many customers Starlink can expect.

In this post, I’ll be going over the potential revenues and expenses Starlink can look forward to, and comparing those to Common Sense Skeptic’s claims.

Part 2 - The Economics

Part 4 - Conclusion and Score

The Realities

SpaceX is going to have to deal with a variety of expenses, including:

Satellite manufacturing

Rocket launches

Dish manufacturing

Selling, General, & Administrative(SG&A) expenses

Research & Development(R&D)

There are a handful of other expenses, but these should cover the ‘big ticket’ expenses.

- Satellite Manufacturing

Starlink Gen 1 is a planned constellation of ~12,000 satellites at various altitudes:

1,584 satellites at 550 km.

1,584 satellites at 540 km.

720 satellites at 570 km.

348 satellites at 560 km.

172 satellites also at 560 km.

SpaceX has also filed for 7,518 satellites operating in Very Low Earth Orbit(VLEO), from 335 to 345 km, using V-band frequencies, bringing the total to just under 12,000.

Now, it’s important to note that SpaceX has also filed for a second-generation constellation(Gen 2) of 30,000 satellites, using Ku-, Ka-, and E-band frequencies.. It is important to keep a distinction between the first 12,000 satellites(Gen 1), and Gen 2, as they will not coexist. For now, we are going to see if the first generation of Starlink can be profitable.

I haven’t been able to verify it, but this is the number Common Sense Skeptic uses for the cost per satellite, so we’ll go with $250,000 per satellite.

A final note about the satellites is that they have a lifespan of 5-7 years, after which they will need to be replaced. For this reason, I will calculate revenues and expenses per 5-7 year ‘cycle’.

- Rocket Launches

While SpaceX has plans to launch Starlink satellites on Starship, that rocket is currently in development and they have to rely on Falcon 9 instead. I will assume all launches will be done on Falcon 9, with a side-note for how Starship could change the costs for this category.

SpaceX executive Christopher Couluris has stated that it “costs $28 million to launch [Falcon 9 Refurbished], that’s with everything.”

*If Starship gets working, the target marginal cost per launch is $2 million, but let’s call that optimistic and calculate with $10 million per launch. Starship will be able to hold 400 satellites in its cargo bay.

- Dish Manufacturing

According to this article, cited by Common Sense Skeptic, each dish(Dishy) initially cost SpaceX $3,000 each, though they have since brought that cost down to $1,300 each. While it is reasonable to assume that economies of scale will bring this figure down further, I will give the skeptics the benefit of the doubt.

SpaceX currently charges customers $499 for the dish, meaning they are lost $801 up-front, per customer.

- SG&A and R&D

It’s difficult to know exactly what these costs will be, but I will be pulling from Viasat revenue percentages that we can use to estimate them. Note that these are additional costs beyond what Common Sense Skeptic used in their video.

Selling, General, and Administrative costs (SG&A) for Viasat average 22% over the past five years.

Research and Development costs (R&D) average 5%.

- Wrapping It All Up

With all the previous assumptions, over a 5-year cycle, we come up with $2 billion in net income with 3 million subscribers:

If the constellation’s lifespan is 7 years, we come up with $7.2 billion in net income with 3 million subscribers:

In an extreme example, with Starship launching, a 7-year lifespan, and reducing the loss per dish to $300, we come up with a $14 billion net income with 3 million subscribers:

For an extreme case on the other side, using all of Common Sense Skeptic’s own numbers, SpaceX needs 5 million subscribers to see profit:

Now, with all of that out of the way, let’s see what Common Sense Skeptic had to say on the economics.

The Claims - Expenses

4:26 - CSS talks about the cost customers have to pay for the dish during the beta($499), as well as speculating on the cost to manufacture. They first show a screenshot from this article, listing an initial manufacturing cost of $3,000 per dish, which has been lowered to $1,500, and more recently, $1,300. All of these numbers come directly from SpaceX, but CSS also says that “according to teardown experts in the field, most likely these units cost the company about $2,000 to manufacture.” That figure, which actually is $2,000 lost per unit, not cost to manufacture, comes from the linked Business Insider article, which says:

“In fact, based on new information received by Business Insider, SpaceX may be eating nearly $2,000 on each one, though it could amortize some of that expense through subscription fees.”

It’s important to note that this BI article is from December 2020, and lines up with another link in CSS’ article from April 2021, which puts the old cost of Dishy at $3,000, or a $2,500 loss per unit. However, for the rest of the video, CSS will use the $2,000 per dish figure, which doesn’t actually come from any of their sources, for their calculations. I will examine the differences in their calculations when the correct, up-to-date numbers are used.

It’s also worth noting that they claim the $2,000 per unit figure is “both middle of the road, and conservative”, while showing a screenshot of yet another article that includes the up-to-date $1,300 figure. In other words, CSS doesn’t use their own sources correctly. They then conclude a $1,500 loss per unit sold, multiplied by 500,000 subscribers, for a $750 million loss. The correct figure would be, assuming no further manufacturing cost drops, a $400 million loss. I’ll address this in more detail when discussion what SpaceX will need to be profitable.

5:22 - CSS starts to talk about the satellites themselves, and an important observation needs to be pointed out. They consistently post screenshots of article headlines and summaries, and use those as the basis of their arguments. The problem is that headlines are designed to be catchy, and often unnuanced or just plain wrong. In this case, they show multiple articles talking about SpaceX’s plan to launch “up to 42,000” satellites, but failing to understand this figure causes compounding errors in future calculations, so it’s time for more background information.

I went over this previously, but it’s worth going over again and adding a little detail. In November 2016, SpaceX filed with the FCC for a non-geostationary orbit satellite system using Ku- and Ka- frequency bands, consisting of 4,425 satellites at altitudes ranging from 1,110 to 1,325 km. Since then, SpaceX has filed many admendments to their original application, and today the constellation stands as thus:

1,584 satellites at 550 km.

1,584 satellites at 540 km.

720 satellites at 570 km.

348 satellites at 560 km.

172 satellites also at 560 km.

This is a total of 4,408, so where does the 42,000 figure come from? Two places.

SpaceX has also filed for 7,518 satellites operating in Very Low Earth Orbit(VLEO), from 335 to 345 km, using V-band frequencies, bringing the total to just under 12,000.

SpaceX has also filed for a second-generation constellation(Gen 2) of 30,000 satellites, using Ku-, Ka-, and E-band frequencies.. It is important to keep a distinction between the first 12,000 satellites(Gen 1), and Gen 2, as they will not coexist.

CSS introduces an error that compounds through their calculations by imposing the costs of not only the current generation constellation, but also its replacement on SpaceX at the same time.

6:06 - CSS makes the observation that no Starlink mission has launched on Falcon Heavy, saying “Wonder why that is?” The reason is simple, Falcon 9 is volume-constrained for Starlink missions, not mass-constrained. Falcon Heavy uses the same fairing, there would be no reason to use it.

When this was brought up in the comments section of their video, CSS claims that “Falcon Heavy has a larger fairing available”, that “…an extended fairing is also supposed to be available for FH”, and “Falcon Heavy [‘s fairing] is the same size in current configuration”. They are referring to a contract SpaceX won, part of which requires a larger fairing. This extended payload fairing is in development, but not yet available.

6:30 - This is where the 42,000 figure is used to come to a terrible conclusion. CSS claims that SpaceX will need to launch Falcon 9 over 700 times. They then show the costs for a Falcon 9 launch, $62 million for a new booster and $50 million for a reused booster, but come to the bizarre conclusion that $55 million is a good compromise. There are two major problems with this.

SpaceX has never launched a Starlink mission on a new Falcon 9 booster.

$50 million is the cost to an external customer and includes company profit. It doesn’t cost SpaceX that much to do the launch. SpaceX executive Christopher Couluris has stated that it “costs $28 million to launch [Falcon 9 Refurbished], that’s with everything.”

CSS tries to justify this by listing expenses that SpaceX would have to cover, including pad lease fees, staff paychecks, and every other associated cost with a launch, but all of those expenses are already priced in.

So CSS multiplies 700 launches by $55 million to come up with a total launch cost of $38.5 billion. A terrifyingly large number, but what does it look like if we plug in the correct numbers?

11,926 satellites means approximately 199 launches at a marginal cost of $28 million each, coming out to a total of $5.572 billion. Quite a difference from CSS’ claim. Even if we wanted to, for some reason, calculate the cost of launching both the Gen 1 and Gen 2 constellations, at $28 million per launch, that would be $19.6 billion, not $38.5 billion. CSS isn’t even close.

7:16 - CSS claims that the reported aspirational costs for the satellites is $250,000 each, citing this article.

A VERY IMPORTANT NOTE ON THIS SECTION OF THE VIDEO!

CSS screenshot the headline for this article, but removed “and Falcon 9 Costs Less than $30 Million”. Why? Because they just finished the section where they claimed Falcon 9 refurbished launches cost SpaceX $55 million each. This is a clear case of intentional dishonesty, rather than so many other instances that could be written off as merely being mistakes. It is far from the only such instance where their motives are obvious as well. Getting back to the topic at hand.

The article lists $250,000 per satellite as an estimate on the part of the author, citing another article which says “CEO Elon Musk and COO Gwynne Shotwell have strongly implied that the per-satellite cost is already well below $500,000”. You can read through the reporting, but none of these figures are aspirational, or direct quotes from a primary source. They are estimates. CSS does use the $250,000 figure for their calculations, but again makes the mistake of attributing the costs for both Gen 1 and Gen 2 constellations. $250,000 x 42,000 satellites = $10.5 billion.

11,926 satellites means a cost of $2.982 billion. Again, CSS is way off.

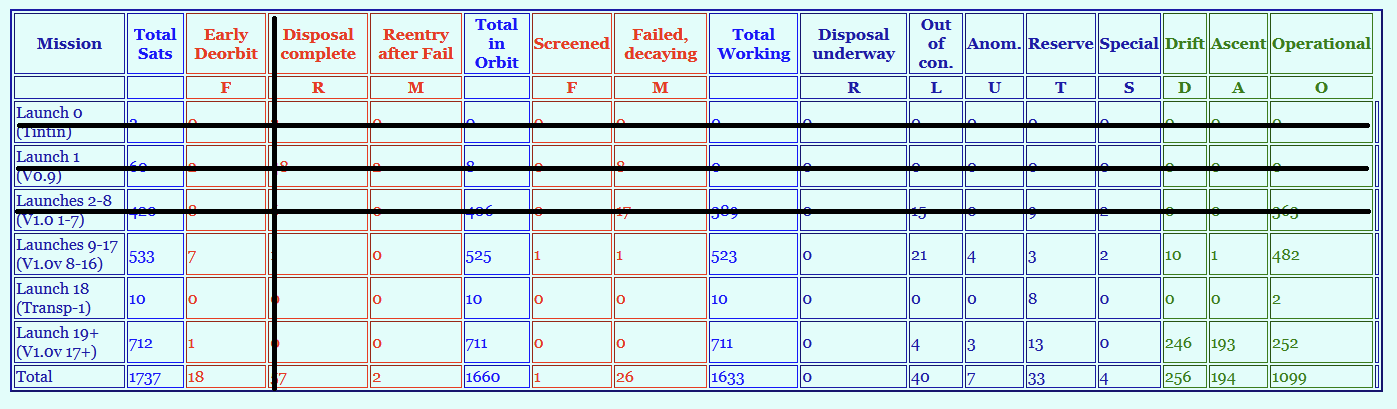

7:39 - CSS cites this article which claims a 3% failure rate for Starlink satellites, but there are several problems with this. Remember, this video was released July 4, 2021. The article in question is from October 2020, and uses data from Jonathan McDowell. (Jonathan has since stopped updating that page and started updating this one (archived as of the date of release of CSS’ video) instead.)

Examining Jonathan’s data, we see several categories.

Early Deorbit - satellites which have reentered; determined to be malfunctioning before reaching operational orbit, and abandoned or actively lowered prior to reentry.

Disposal - satellites which reached the operational orbit but whose orbits were later lowered to cause early reentry. These satellites retained propulsive capability but either failed in some other respect or were deliberately retired.

Reentry after Fail - Reentered after an extended period of uncontrolled orbital decay; presumed failed.

Screened - Satellites not working correctly and left in low orbit prior to completing orbit raising; expected to reenter soon.

Failed - Satellites stopped stationkeeping after reaching operational orbit; no manuevers occurring, presumed failed.

A little more background on Starlink. The satellites are launched up into an orbit at ~292 km where they are released from the second stage. From there, they spread out and use their onboard thrusters to push themselves up to their final orbits. For these categories, “low orbit” and “before reaching operational orbit” means we are talking about satellites around this mark, ~300 km. At this altitude, if a satellite fails, it will deorbit in a matter of weeks. At the ~550 km operational orbits, it can instead take years for an uncontrolled satellite to deorbit.

So for a satellite to be considered failed, it needs to fall into the Early Deorbit, Reentry after Fail, Screened, or Failed categories. Disposal were satellites that remained operational, and we can’t always say why they were disposed. For example, the satellites from launches 0 and 1 were all prototypes and deliberately deorbited after testing.

Back to the video, CSS says “The current failure rate of the Starlink constellation in orbit is 3%, and most of them are less than a year old.” This is extremely misleading, for the following reasons:

Most of the satellites that are less than a year old haven’t failed. Starlink satellites launched after July 4, 2020, start with Starlink launch #10. Looking at Jonathan’s page, launches are broken up by number. We have to include launch #9, but it’s close enough. Looking at only the satellites less than a year old, how many have failed? 8 Early Deorbits, 1 Screened, and 1 Failed Decaying, for a total of 10 satellite failures among those less than a year old, or a 0.79% failure rate.

Ignoring the “less than a year old” line, CSS makes the mistake of turning the total lifetime “failure” rate into an annual failure rate. The truth is, we won’t have a good idea of the failure rate until the V1 satellites have been in orbit for much longer than they have been, at which time they will have been replaced by V1.5 and V2 satellites, so again we won’t really know. Regardless, it appears that the failure rate is dropping significantly as SpaceX continues to develop their hardware.

Let’s go with a 1% per year failure rate. For the Gen 1 constellation, that would require an additional 120 satellites per year, and two launches, or $86 million per year, a far cry from CSS’ $1.5 billion annually.

Conclusion: Expenses

Because the lifespan of Starlink satellites is 5-7 years, I will be calculating the total costs for everything over a 5-year cycle. If SpaceX keeps a constellation up for 7 years, the numbers will only be more beneficial for them, but I’ll give the skeptics the benefit of the doubt. CSS comes up with a total cost for satellites and launches of $56.35 billion, where the correct figure is a much more reasonable $8.98 billion.

This certainly doesn’t tell the whole story, I went into a lot more detail earlier in this post, but it does show just how far off-track CSS is, while only 8 minutes into the video.

The Claims - Revenues

25:25 - CSS returns to the economics, addressing the global market for satellite internet. “In a recent interview, Gwynne Shotwell indicated that Starlink is looking to tap into what she described as a trillion-dollar market with their satellite network.” CSS then shows $1 trillion on the screen, and 7.8 billion for the population of the planet, and concludes that Shotwell, “personal ventriloquist dummy”, thinks that SpaceX is going to extract $127/year out of every man, woman, and child on the planet.

I don’t imagine I have to explain why this is a completely asinine claim to make, but I’ll do it anyway. CSS shows this article, but only extracts the $1 trillion figure and misrepresents it wildly. Here is what she actually said:

“The total addressable market for launch, with a conservative outlook on commercial human passengers, is probably about $6 billion. But the addressable market for global broadband is $1 trillion. If you want to help fund long term Mars development programs, you want to go into markets and sectors that are much bigger than the one you're in, especially if there's enough connective tissue between that giant market, and what you're doing now.”

She didn’t claim that SpaceX was going to capture the entire global broadband market, she simply said they were going to move into competing in that market, yet CSS uses this opportunity to insult Shotwell using their strawman claim, and the insults don’t stop there.

After showing a map of average income by country, CSS has this to say. “If Miss Shotwell thinks she will be selling $500 signal boxes, and $100 per month subscriptions to these large populations of people, she needs to give that blond wig a shake.” while showing a picture of one of her yearbook photos where she had dark hair. This is not the first, nor the last time CSS has made disparaging remarks regarding a woman’s appearance, or used a woman’s gender to try to make a point.

27:15 - CSS then brings back the map and determines they will remove all of the countries in red. The main problem with this is that CSS is dismissing out of hand:

Outliers. While the average income in these countries is low, that doesn’t mean nobody can afford satellite internet. Perhaps the top 10%, or 1% will be the target customer, but they still exist.

Alternative revenue streams. Direct-to-residental isn’t the only way to market internet satellite. Starlink can serve businesses, or server larger groups of people in a group, or by acting as the backhaul for a local ISP or distribution point. There is already precedent for this among indigenous people around the globe, and SpaceX has announced multiple deals already with telecommunications partners.

Subsidies, grants, or other forms of assistance. Wales has a program that can entirely pay the $500 equipment fee for getting Starlink, as an example.

Regardless, CSS removes the countries in red, then claims none of the remaining countries need satellite internet because “every single one of those countries is already serviced with global broadband internet through the existing oceanic cable system.” By this claim, every single person in America, Canada, and Latin America should have access to wired broadband, but that is simply not the case. As I said in the first post on this video, there are roughly 1.7 million people in the US, 1.5 million in Canada, and 0.5 million in Latin American who already pay for Viasat or HughesNet satellite(which I have demonstrated is not a competitive service). In addition, the FCC has found that 19 million Americans don’t have access to a single broadband service, but CSS would have you believe everybody does.

28:05 - CSS shows a screenshot of this release. As an aside, they claim to always cite their sources, but this simply isn’t true. Very often they leave off any citation, and when they do include a citation, it is usually simply the name of the organization, rather than providing enough information that someone could easily find their source and double-check.

That mini-rant aside, this report doesn’t include Starlink at all. It is a report of expected growth for existing geo-satellite internet providers, using their historical data. “The research covers the current Commercial Satellite Broadband market size of the market and its growth rates based on 6-year records with company outline of Key players/manufacturers”

As I have shown in my previous post, it’s not a surprise that the satellite internet industry hasn’t been set for amazing growth before Starlink. Who wants to pay over $100/month for a 12 mbps connection with a 35 GB monthly data cap and 643 ms latency? I’m honestly surprised there are as many subscribers as there are, but having once been in the position where my options were HughesNet or dial-up, I understand the struggle.

The reality is that this report simply is not a good indicator of Starlink’s potential market. Regardless, CSS is also wrong about their conclusion. “So if Ms. Shotwell captured the entire global satellite industry, put everyone else out of business and stood alone as the sole provider of satellite internet in the world, she would manage to make about one half of one percent the amount of money she says Starlink is poised to create for her boss.” This is said while the $1 trillion number is displayed on the screen, which we know is incorrect. SpaceX has said, publicly, that they are targeting $30 billion in annual revenue. Never have they said they are targeting anywhere near $1 trillion.

Now, would Starlink be profitable if they did capture the entire existing satellite internet market? The cited study lists the market at $3.424 billion in 2019, growing to $6.896 billion by 2026. Even just using the lower figure, we nearly hit the 3 million subscriber mark I described earlier. $17.12 billion in revenue every 5 years for approximately $1.1 billion in net profit. Going by the projected 2026 number, SpaceX would be looking at somewhere around $12 billion in profit.

28:51 - CSS addresses the topic of federal subsidies: “Anyone taking a hard look at the numbers can determine pretty quickly that they just do not add up. You’d have to be completely oblivious to give Musk any money for this at all. You’d have to be almost as clueless as… the federal government.” They then bring up the nearly $900 million SpaceX won of the $20.4 billion Rural Digital Opportunities Fund auction, the government’s project to bring broadband internet to the previously mentioned 19 million Americans who don’t have access to any. They then criticize Musk for taking advantage of government subsidies, but no mention at all of the other companies that also won funds under this auction.

CSS then divides the award into the number of locations SpaceX needs to service, 642,925 locations, to come up with a per-location award of $1,380, but that’s not how Starlink works. It doesn’t cost SpaceX any more money to service 10 million locations than it costs them to service 600,000 locations.

29:55 - CSS talks about the requirements Starlink has to meet to be eligible to collect that award money. It’s performance-based, not an up-front payment. SpaceX has to provide:

80% of locations above 80 mbps download speed.

95% of locations below 100 ms latency.

They go off on a tangent about how the FCC wasn’t initially convinced that Starlink would be able to meet these criteria, but the FCC dropped those concerns after SpaceX responded and they were allowed to compete.

CSS then cites a report based off of information released by Ookla that showed the average performance of speedtest.net tests for Starlink beta testers during Q1 2021. While it’s true that Starlink at that point wasn’t providing the performance the RDOF program requires at the end of six years, CSS doesn’t mention this part of Ookla’s report:

“Starlink meets minimum tier for FCC’s Rural Development Opportunity Fund”

At the time of Ookla’s report, SpaceX hadn’t even finished launching the first shell of satellites that would provide basic, but global coverage. That shell is expected to be fully-deployed around September 2021.

CSS characterizes this report as Ookla claiming “the system might eventually qualify for the upload speeds, but is already falling well short on the download speeds. Meaning that Starlink won’t qualify for the RDOF subsidy, because they will not hit the benchmarks.” This is odd that CSS is putting words in Ookla’s mouth, rather than quoting their report:

“Given this data, it's safe to say Starlink could be a cost-effective solution that dramatically improves rural broadband access without having to lay thousands of miles of fiber.”

Regardless, it is interesting to note Ookla’s Q2 2021 report on Starlink, showing that the average download speed for Starlink users is now 97.23 mbps, average upload is 13.89 mbps, and latency of 45 mbps. This is already enough to qualify for the download speeds and latency, though not the upload speed requirement of 20 mbps.

My question is, will CSS report on this Ookla report? I doubt it, they haven’t so far, and it directly contradicts their prediction that Starlink would never hit these benchmarks.

Conclusion - Revenues

SpaceX’s market in the US alone is over 19 million people, and as I demonstrated in the first post, they won’t struggle competiting with HughesNet and Viasat. Since Starlink will likely be a profitable venture with only 3 million subscribers globally, it seems to be far more viable than Common Sense Skeptic would have you believe.

Part 2 - The Economics

Part 4 - Conclusion and Score

Dude, you need to make a youtube channel. You should expose these vitrolic morons for the conmen that they trully are.

If you look at little's other starlink debunking of ThunderF00t, they think 1.35 Mbps is something people will pay $100 for.

Morons "exposing" "morons". Moronic. Don't even need to run calculations on this, little dug their own grave. YouTube will only bring little's stupidity to the masses.